Travels with Charley: In Search of America is mainly what they call a travelogue o travel literature. It’s not the first time that I read one and I’m starting to enjoy the genre. I added this one to my want to read in Goodreads a long time ago after reading some hilarious paragraphs during a couple of English lessons, and the rest of the book had not disappointed me at all.

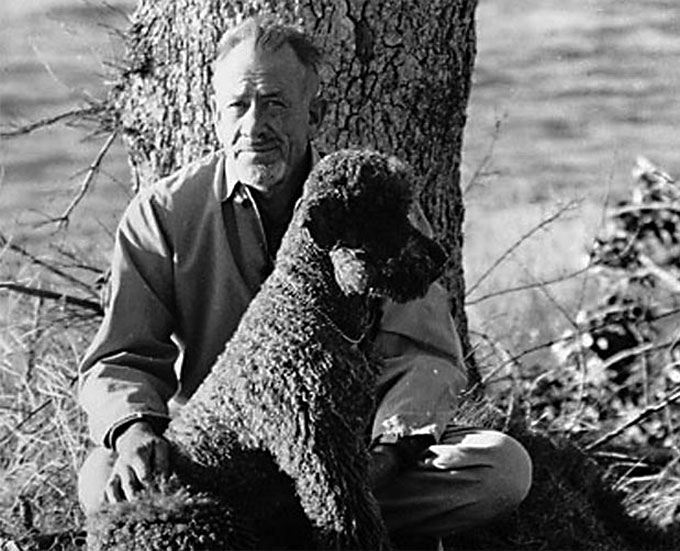

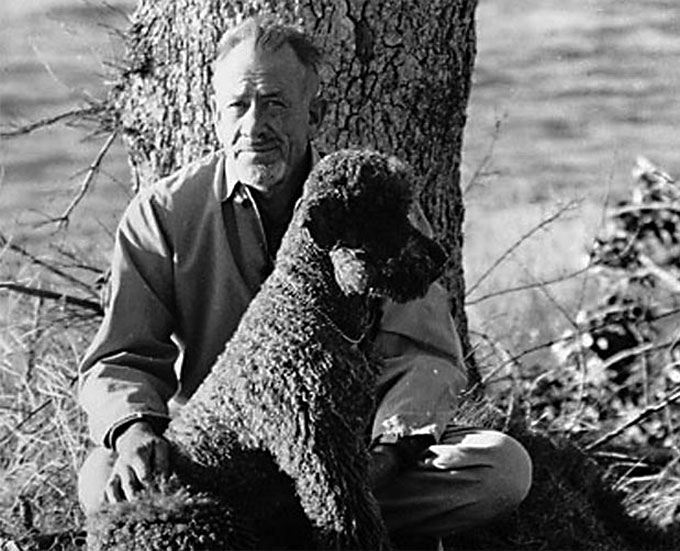

John Steinbeck and Charley

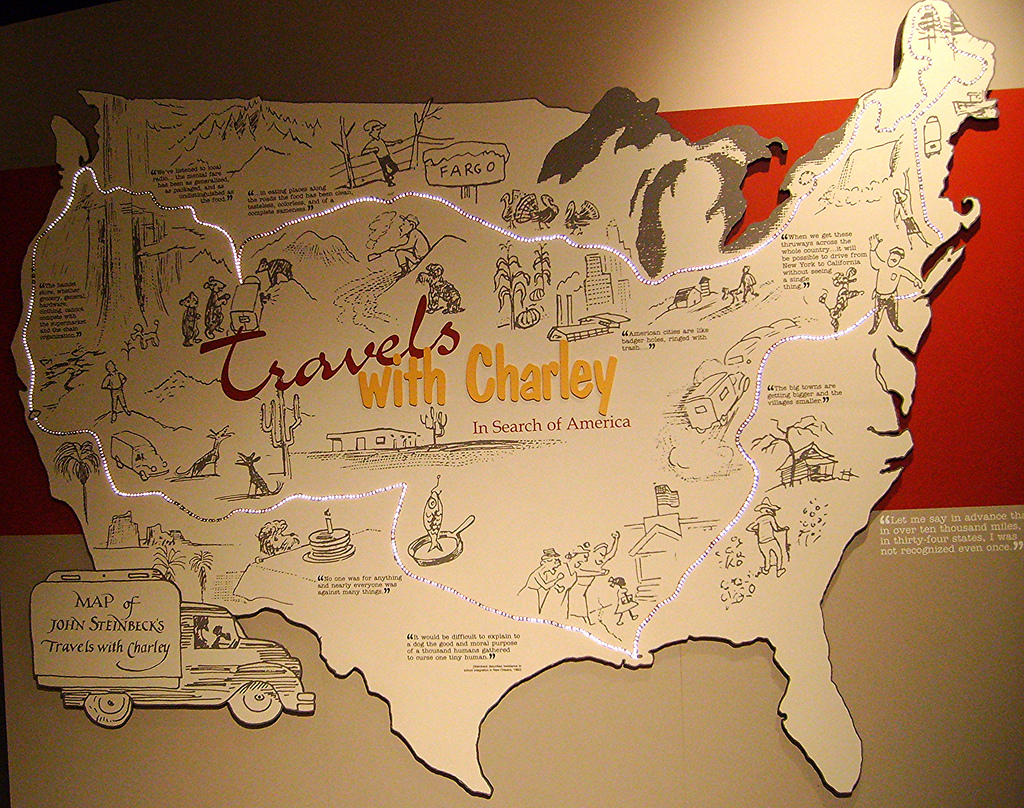

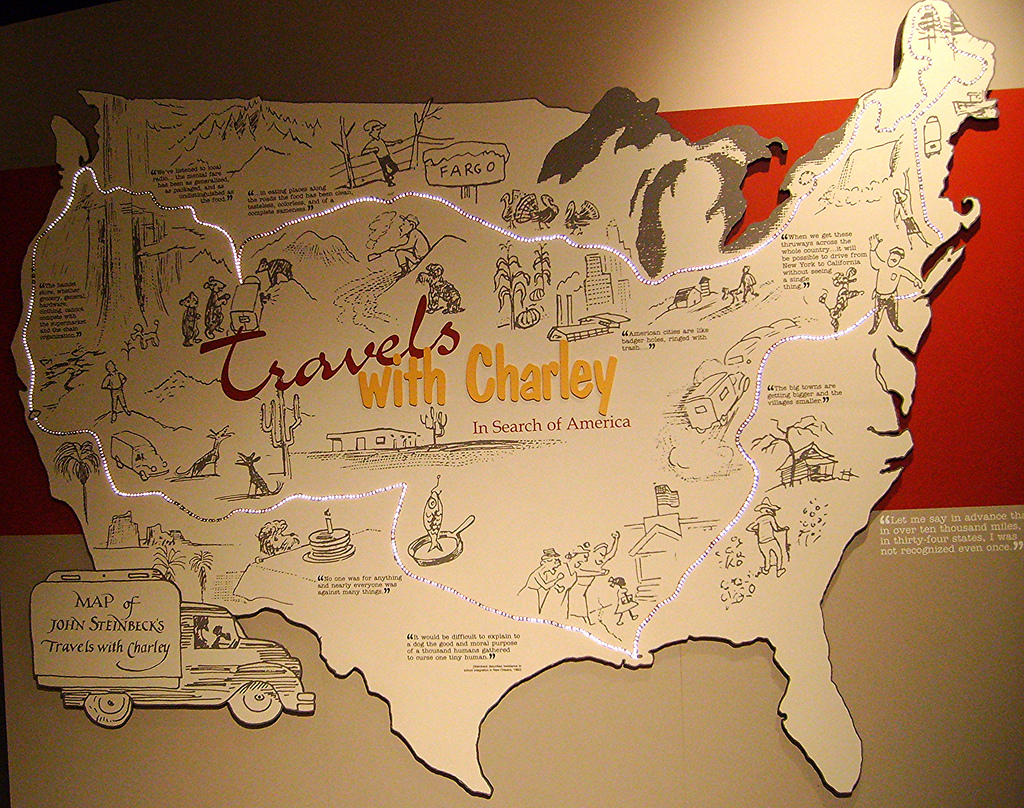

In 1960, a 58 years old John Steinbeck bought a small camper to drive around the United States with his dog (Charley). He called the camper Rocinante (here you have a picture of it), the perfect name for a saddle in which to go on adventures. He said before the book was published:

I was advised that the name Rocinante painted on the side of my truck in sixteenth-century Spanish script would cause curiosity and inquiry in some places. I do not know how many people recognized the name, but surely no one ever asked about it.

The book was published in 1962 and Steinbeck died just six years later. Reading this book you can somehow perceive his age, obviously regarding his health condition but also because he didn’t care about others reading what he wrote or did. When he started the arrangements for the trip, everyone tried to persuade him to abandon the idea because it’s age and chronic disease, but he felt he needed the trip and that it was now or never.

During the previous winter I had become rather seriously ill with one of those carefully named difficulties which are the whispers of approaching age. When I came out of it I received the usual lecture about slowing up, losing weight, limiting the cholesterol intake. It happens to many men, and I think doctors have memorized the litany. It had happened to so many of my friends. The lecture ends, “Slow down. You’re not as young as you once were.” And I had seen so many begin to pack their lives in cotton wool, smother their impulses, hood their passions, and gradually retire from their manhood into a kind of spiritual and physical semi-invalidism. In this they are encouraged by wives and relatives, and it’s such a sweet trap. Who doesn’t like to be a center for concern? A kind of second childhood falls on so many men. They trade their violence for the promise of a small increase of life span. In effect, the head of the house becomes the youngest child. And I have searched myself for this possibility with a kind of horror. For I have always lived violently, drunk hugely, eaten too much or not at all, slept around the clock or missed two nights of sleeping, worked too hard and too long in glory, or slobbed for a time in utter laziness. I’ve lifted, pulled, chopped, climbed, made love with joy and taken my hangovers as a consequence, not as a punishment. I did not want to surrender fierceness for a small gain in yardage. My wife married a man; I saw no reason why she should inherit a baby.

The purpose of the trip was to get to know again his country and, in my opinion, as a way to say goodbye to several places, essential locations for him in the past. This quote summarizes his motivations:

For many years I have traveled in many parts of the world. In America I live in New York, or dip into Chicago, or San Francisco. But New York is no more America than Paris is France or London is England. Thus I discovered that I did not know my own country. I, an American writer, writing about America, was working from memory, and the memory is at best a faulty, warpy reservoir. I had not heard the speech of America, smelled the grass and trees and sewage, seen its hills and water, its color and quality of light. I knew the changes only from books and newspapers. But more than this, I had not felt the country for twenty-five years. In short, I was writing of something I did not know about, and it seems to me that in a so-called writer this is criminal. My memories were distorted by twenty-five intervening years.

Steinbeck beautifully describes his feelings about the places or about the people he encountered, and that is what makes this book remarkable. He takes advantage of the trip circumstances to give his opinion on the social and political issues of 1960: decisive election year between Nixon and Kennedy, the embarrassing (even on those days for him) racial issues in the southern states and the cold war against the Soviet Union, just to give some examples.

As one can imagine reading the book, and it was confirmed some years after the publication, some of the dialogues during his encounters are purely fictional as a mean for the author to describe a situation or a way of thinking of the folks he encountered. Part of the magic resides in guessing which ones are more or less distant from his real experiences. He even describes the approach as a disclaimer:

I've always admired those reporters who can descend on an area, talk to key people, ask key questions, take samplings of opinions, and then set down an orderly report very like a road map. I envy this technique and at the same time do not trust it as a mirror of reality. I feel that there are too many realities. What I set down here is true until someone else passes that way and rearranges the world in his own style.

The book contains dozens of brilliant quotes, some of them with a beautiful and intense description that mentally transfers the reader to a certain American landscape:

The redwoods, once seen, leave a mark or create a vision that stays with you always. No one has ever successfully painted or photographed a redwood tree. The feeling they produce is not transferable. From them comes silence and awe. It's not only their unbelievable stature, nor the color which seems to shift and vary under your eyes, no, they are not like any trees we know, they are ambassadors from another time. They have the mystery of ferns that disappeared a million years ago into the coal of the carboniferous era. They carry their own light and shade. The vainest, most slap-happy and irreverent of men, in the presence of redwoods, goes under a spell of wonder and respect.

You cannot use this book to prepare a similar trip, or to discover any of the places that he visited. He also wrote about it in the last part of the book, as a retrospective of what he finally ended writing, in one of my favorite quotes of the book:

If an Englishman or a Frenchman or an Italian should travel my route, see what I saw, hear what I heard, their stored pictures would be not only different from mine but equally different from one another. If other Americans reading this account should feel it true, that agreement would only mean that we are alike in our Americanness. From start to finish I found no strangers. If I had, I might be able to report them more objectively. But these are my people and this my country. If I found matters to criticize and to deplore, they were tendencies equally present in myself. If I were to prepare one immaculately inspected generality it would be this: For all of our enormous geographic range, for all of our sectionalism, for all of our interwoven breeds drawn from every part of the ethnic world, we are a nation, a new breed. Americans are much more American than they are Northerners, Southerners, Westerners, or Easterners. And descendants of English, Irish, Italian, Jewish, German, Polish are essentially American. This is not patriotic whoop-de-do; it is carefully observed fact. California Chinese, Boston Irish, Wisconsin German, yes, and Alabama Negroes, have more in common than they have apart. And this is the more remarkable because it has happened so quickly. It is a fact that Americans from all sections and of all racial extractions are more alike than the Welsh are like the English, the Lancashireman like the Cockney, or for that matter the Lowland Scot like the Highlander. It is astonishing that this has happened in less than two hundred years and most of it in the last fifty. The American identity is an exact and provable thing.

I really liked this book, and for sure I’ll try to read more from Steinbeck.