Acabo de terminar la lectura de Fermat's Last Theorem (El último teorema de Fermat en su edición española) del autor británico Simon L. Singh. A pesar de haber tardado bastante en acabarlo (diversos líos me han tenido alejado de cualquier libro) me ha parecido una lectura muy amena y totalmente recomendable. Antes de seguir, debo indicar que este libro lo conseguí en la pasada TAM London 2010 firmado por el propio autor.

Simon Lehna Singh, galardonado con la Orden del Imperio Británico, es conocido principalmente por sus trabajos acerca de ciencia y matemáticas. Sus obras más importantes son ésta sobre el último teorema de Fermat, The Code Book (sobre criptografía), Big Bang (sobre el origen del universo, que regalé también firmado a un buen amigo) y su última publicación Trick or Treatment? Alternative Medicine on Trial (sobre los peligros de la medicina alternativa).

Fue además conocido por la ciudadanía británica y por los escépticos de todo el mundo tras ganar su juicio contra la British Chiropractic Association (Asociación Quiropráctica Británica), que le demandó por difamación por una columna de Singh en The Guardian en la que éste indicaba que dicha asociación "promovía alegremente tratamientos falsos" ("happily promote bogus treatments", me encanta la frase original). La sentencia absolvió a Singh y además desembocó en una oleada de demandas ciudadanas por publicidad engañosa contra más de 500 quiroprácticos, y en la obligatoriedad a la asociación de retirar de todas las webs y clínicas de sus asociados cualquier referencia a tratamientos curativos que no tuvieran eficacia demostrada. Es decir, todos ellos.

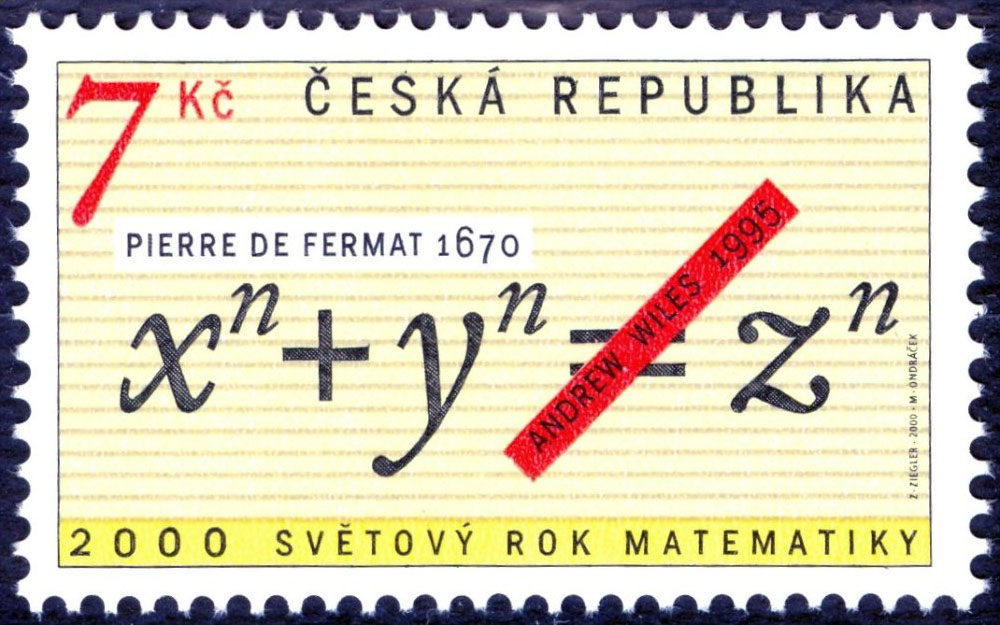

Volviendo a la obra, en este caso Singh narra la búsqueda por parte de la comunidad matemática mundial durante más de 350 años de una prueba para el último Teorema de Pierre de Fermat, abogado francés del siglo XVII que como matemático amateur consiguió ser (y sigue siendo aún ahora) toda una referencia. Además de su extensa producción, ha pasado a la historia por este último teorema y su leyenda, siendo considerado como el problema matemático más difícil hasta que Andrew Wiles lo consiguió probar en 1995.

El último teorema de Fermat, brevemente, se puede enunciar diciendo que siendo n un número entero mayor que 2, entonces no existen números naturales a, b y c, tales que se cumpla an + bn = cn. Este enunciado aparentemente simple se resistió durante siglos a varias generaciones.

Además de su dificultad, se hizo más grande y desafiante aún dado que el propio Fermat, poco amigo de compartir sus investigaciones, lo conjeturó en el margen de un ejemplar de Arithmética (de Diofanto de Alejandría) afirmando de su puño y letra que tenía la prueba para el teorema pero era demasiado grande para incluirla en dicho margen. Tremendo humor, y tremenda ira para aquellos que no eran muy aficionados a Fermat.

El libro va narrando capítulo a capítulo toda esta mítica historia, desde el propio Fermat y su compleja relación con sus contemporáneos, pasando por los principales intentos posteriores de probar dicho teorema hasta llegar al intento definitivo por parte de Andrew Wiles tras más de 6 años de dedicación exclusiva en secreto.

Como introducción, antes de entrar en la propia historia, el autor explica de forma tremendamente clara, didáctica y (milagrosamente) amena ciertos conceptos básicos de matemática teórica. De estas primeras páginas he extraído un fragmento que os resultará interesante, más allá de la propia historia del Teorema.

Absolute Proof

The story of Fermat's Last Theorem revolves around the search for a missing proof. Mathematical proof is far more powerful and rigorous than the concept of proof we casually use in our everyday language, or even the concept of proof as understood by physicists or chemists. The difference between scientific and mathematical proof is both subtle and profound, and is crucial to understanding the work of every mathematician since Pythagoras.

The idea of a classic mathematical proof is to begin with a series of axioms, statements that can be assumed to be true or that are self-evidently true. Then by arguing logically, step by step, it is possible to arrive at a conclusion. If the axioms are correct and the logic is flawless, then the conclusion will be undeniable. This conclusion is the theorem.

Mathematical theorems rely on this logical process and once proven are true until the end of time. Mathematical proofs are absolute. To appreciate the value of such proofs they should be compared with their poor relation, the scientific proof. In science a hypothesis is put forward to explain a physical phenomenon. If observations of the phenomenon compare well with the hypothesis, this becomes evidence in favor of it. Furthermore, the hypothesis should not merely describe a known phenomenon, but predict the results of other phenomena. Experiments may be performed to test the predictive power of the hypothesis, and if it continues to be successful then this is even more evidence to back the hypothesis. Eventually the amount of evidence may be overwhelming and the hypothesis becomes accepted as a scientific theory.

However, the scientific theory can never be proved to the same absolute level of a mathematical theorem: It is merely considered highly likely based on the evidence available. So-called scientific proof relies on observation and perception, both of which are fallible and provide only approximations to the truth. As Bertrand Russell pointed out: "Although this may seem a paradox, all exact science is dominated by the idea of approximation." Even the most widely accepted scientific "proofs" always have a small element of doubt in them. Sometimes this doubt diminishes, although it never disappears completely, while on other occasions the proof is ultimately shown to be wrong. This weakness in scientific proof leads to scientific revolutions in which one theory that was assumed to be correct is replaced with another theory, which may be merely a refinement of the original theory, or which may be a complete contradiction.